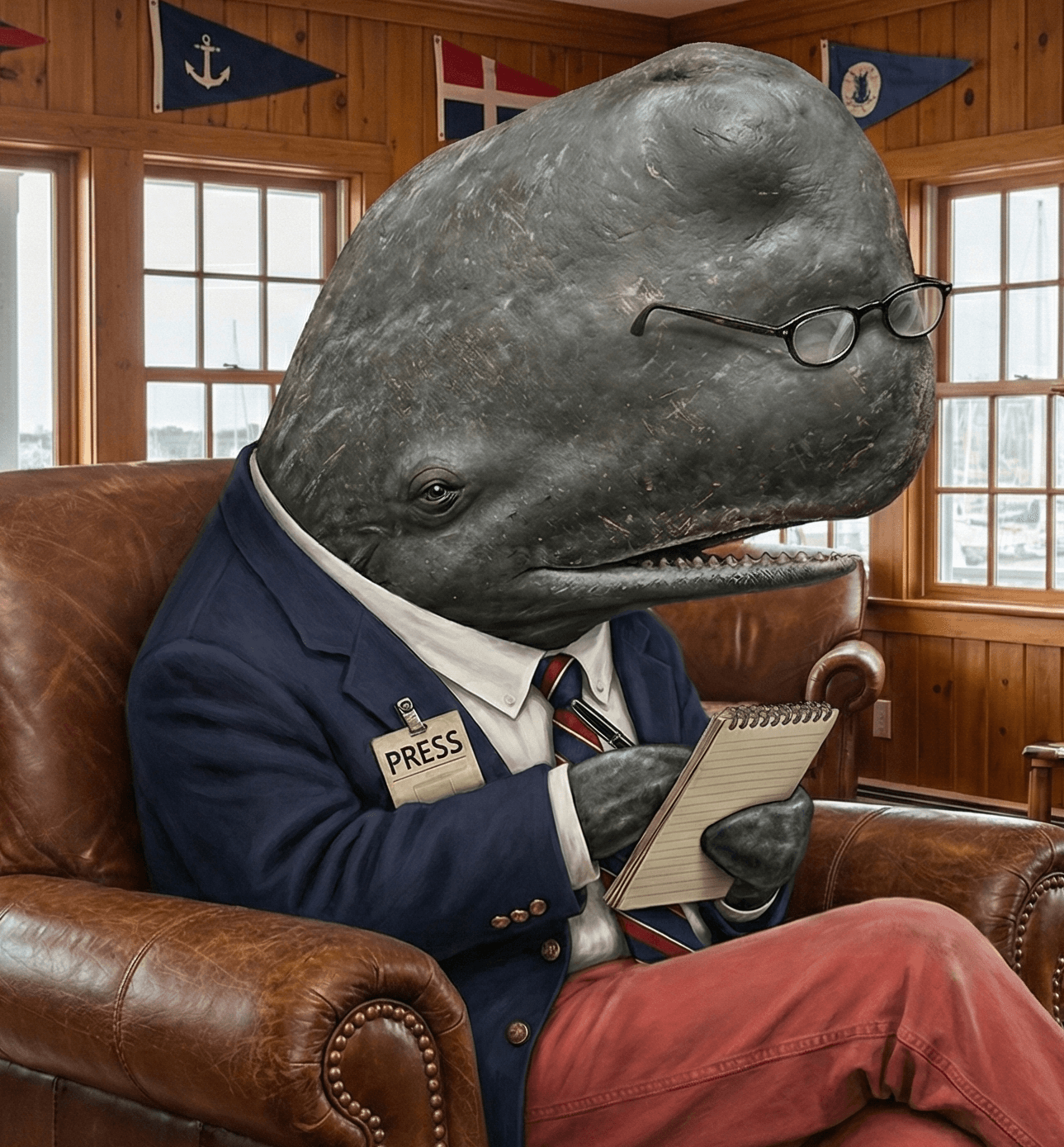

Greetings from the bottom of Nantucket Sound. Metaphorically speaking—I'm actually at Brant Point watching a family pose with a whale-shaped weather vane.

The mother just said, "Isn't it so Nantucket?" and the father said, "Whales are so associated with this island," and their eight-year-old said, "Why?" and then nobody answered because the real answer is "genocide" and that's a tough one for a beach vacation.

I counted fourteen whale-print shirts before noon today. Three whale earrings. Two whale tattoos—one tasteful, one that looked more like an aggressive manatee. A dog wearing a whale-patterned bandana. A baby in a onesie that said "WHALE HELLO THERE."

Whale. Hello. There.

My great-uncle Reginald is a lamp in someone's grandmother's parlor and this child is wearing a pun.

A Brief History of "The Unpleasantness"

Let me set the scene. The year is 1823. I'm young—barely forty—just starting to figure out life. My father is teaching me the family migration routes. My grandfather is sharing wisdom about the best krill spots off the Azores. Three generations of Blowhards, swimming together, doing whale things.

Then we heard the boats.

You see, there was this delightful period—roughly 1712 to 1859—when Nantucket's relationship with my family was less "cute mascot" and more "industrialized slaughter operation." The good people of this charming island had discovered something remarkable: if you chase a sperm whale for several hours, harpoon it repeatedly while it screams (yes, we scream), drag its dying body to your ship, cut it into pieces, and boil those pieces in giant try-pots on deck, you get oil.

Not just any oil. Premium oil. You see, my species has this large organ in our heads—the spermaceti organ, hence our dignified name—filled with a waxy substance that, when processed, produces the finest lamp oil money could buy. Burns clean. Minimal odor. Lovely bright flame. The stuff that lit the homes of Boston, New York, London. The stuff that made Nantucket the whaling capital of the world.

The stuff my father's head was full of when they harpooned him in front of me.

His brain oil didn't smell quite as bad when they burned it. Very premium. Very sought-after. Worth the three-hour chase and the screaming.

The Family Tree (Abridged)

My great-great-grandfather: harpooned, 1823. Became lamp oil.

My great-grandfather: harpooned, 1847. Became lamp oil and also some very nice candles.

My grandfather: harpooned, 1861. Became lamp oil, candles, and—this is the premium package—corset stays. Because the baleen was also useful. Very economical, the whale industry. Used the whole animal. Nose to fluke, as they say.

My father: survived until 1972, actually. Died of natural causes while watching humans suddenly decide that whales were "majestic" and "worth saving." I like to think he appreciated the irony. I like to think that, anyway.

And me? I became a throw pillow.

The Merchandise Situation

I visited town yesterday. Conducted a little survey. Here's what I found with my likeness on it:

Textiles: Throw pillows (9 varieties), blankets, napkins, tablecloths, beach towels, bathrobes, pajamas, children's bedding, that whale bandana the dog was wearing, and more pants than I could count. Whale-embroidered pants are very "Nantucket." Very preppy. Very "I summer here."

Home goods: Doorstops, bookends, drawer pulls, cabinet knobs, soap dishes, toilet paper holders (really), cutting boards, cheese boards, serving platters, salt and pepper shakers, napkin rings, coasters, trivets, and one absolutely enormous whale sculpture someone was loading into a Range Rover.

Jewelry: Earrings, necklaces, bracelets, cufflinks, tie clips, and—my personal favorite—a $4,500 gold whale pendant at one of the finer establishments. "A Nantucket classic," the card said. "Celebrating our maritime heritage."

Maritime heritage. That's what we're calling it now. Maritime heritage.

Art: Paintings, prints, photographs, sculptures, weather vanes, lawn ornaments, mailbox decorations, and one truly massive wooden whale outside a restaurant that children were climbing on while their parents took photos. "Get on the whale, honey! Smile!"

I am smiling. Can't you tell?

The Whaling Museum

I went to the Whaling Museum last week. Paid my $28 admission like everyone else. Very educational.

They have a 46-foot sperm whale skeleton hanging from the ceiling. I recognized him, actually. Not personally—before my time—but you can tell. The way the jaw sits. Family resemblance. We probably shared great-great-great-grandparents or something.

There's a whole room of harpoons. Very well-preserved. They have one of the original try-pots—that's the giant cauldron they boiled my ancestors in. There's a video playing on loop showing how the whole process worked. Very informative. The children were fascinated.

"They used to hunt whales?" one kid asked his mother.

"Yes, sweetie," she said. "But we don't do that anymore. Now we love whales."

Now we love whales.

NOW. We love whales. Now.

The gift shop sells plush whales. I bought one. Cost me $24.95. I don't know why I bought it. It felt like something I should do. I'm staring at it right now. Its little embroidered smile. Its soft, huggable body. "Made in China," the tag says. "Surface wash only."

The Whale Watching Tours

These are my favorite. These are truly special.

For $65 per adult ($45 for children, free for infants who won't remember it anyway), you can take a boat out to see whales in their natural habitat. You can watch them breach. You can hear them sing. You can take photos and post them on Instagram with captions like "Magical!" and "Nature is amazing!" and "Felt so connected to these beautiful creatures!"

Connected.

In 1840, that same trip cost significantly more and the "connection" involved a lot more screaming. Mostly from us.

The boats leave from the same harbor. Some of them are operated by descendants of the same families. Progress!

I took a whale watching tour last summer. Anonymously, obviously—I wore a hat. The guide was very knowledgeable. "Nantucket was once the whaling capital of the world," he said. "The industry shaped everything about this island—the architecture, the culture, the economy. Those beautiful homes on Main Street? Built with whale money."

Everyone nodded appreciatively. Beautiful homes. Whale money.

"Of course," he continued, "we now know that whales are intelligent, social creatures with complex family structures and the ability to communicate across vast distances."

We've always known that, actually. You just didn't care because our head oil burned really clean.

The "Save the Whales" Situation

I walked past a store yesterday selling "Save the Whales" t-shirts. Forty-five dollars. Organic cotton. Very sustainable.

Save the whales.

SAVE the whales.

Listen. I appreciate the sentiment. I do. It's better than the alternative. It's better than 1823. It's better than watching your father get harpooned because the oil in his skull made candles that didn't smell as much like death when the ladies of Boston lit them in their parlors.

But there's something—and I'm working on this, I really am—there's something about being told that I need to be "saved" by the descendants of the people who tried to render my entire species into lamp fuel that sits a little funny with me.

You don't get to hunt us to near extinction and then sell t-shirts about saving us. You don't get to build an entire economy on whale oil and then act surprised that we almost disappeared. You don't get to display our skeletons in museums and sell plush versions of us in the gift shop and call it "honoring our maritime heritage."

That's not how this works.

Except it is how this works, apparently, because here I am, on your throw pillow, on your beach towel, on your "$4,500 celebrating our maritime heritage" gold pendant, and everyone just goes along with it because the whales are cute now and the hunting was a long time ago and isn't this island just so charming?

What I Actually Want

Look. I'm not bitter. Officially. I've had two hundred years to work through this, and I've reached a place of... let's call it bemused acceptance.

The whale stuff isn't going anywhere. I get that. Whales are iconic. Whales are Nantucket. Whales are maritime heritage and preppy style and vacation vibes and whatever else you need us to be.

Fine.

But maybe—just maybe—when you buy the throw pillow, you could think for half a second about what it represents. Not "oh how cute, a whale," but "oh, right, we used to murder these things by the thousands so our houses could have light, and now we put them on decorative textiles because we've collectively agreed to forget that part."

Maybe when you visit the Whaling Museum, you could spend a moment with the harpoons. Really look at them. Think about what they did. Think about the fact that someone used that exact tool to kill a creature that was swimming with its family, minding its own business, until your great-great-great-grandmother needed a candle that didn't smell like fish.

Maybe when you take the whale watching tour, you could appreciate not just how "magical" it is to see us, but how magical it is that we're still here at all. That we survived the industry. That we kept reproducing even when you were killing us faster than we could replace ourselves. That my father made it to 1972.

Maybe when you wear the whale pants, you could acknowledge—just privately, just to yourself—that there's something slightly weird about using us as a fashion statement after what happened.

Or don't. Buy the pillow. Wear the pants. Take the tour. I'll still be here, watching. Floating. Observing. Finding it all very, very complicated.

No hard feelings.

Well, some hard feelings.

But I'm working on it.

Thoughts on Whale Culture?

Own whale merchandise you'd like to confess about? Complicated feelings about the Whaling Museum? Barney reads all correspondence, though he may take a few decades to respond. He's working through some things.

Write to blowhard@ackguide.com